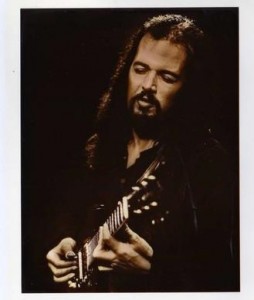

Leonard Harold “Lenny” Breau (Photo courtesy and permission of Art of Life Records.†)

Lenny, how would you describe your music? In what terms?

Well, if I had to say something fast, I have to say, “It’s just music.” You see? But it’s a combination of all the different kinds of music that I learned—all the country music years and the jazz clubs and the flamenco records I listened to and the east Indian records—it’s a combination of all of that I liked to inject into my jazz playing. So it would be hard to have one name for it, you know what I mean?

— Lenny Breau (1968 half–hour film documentary)

When I first met Lenny Breau, I was in the deepest funk of my life.

I have written briefly of this time before in this blog. Basically, my solo concert career as a classical guitarist had irrevocably crashed due to personal health issues. I had an essential tremor (and still do) that affected my whole body. It was particularly dreadful on my fine motor coordination, and also seriously affected the way in which I process information and express myself musically and verbally.

I was on the edge of attaining national recognition for my playing. I had to give up a lucrative concert and performing career and cancel any recording sessions that I had scheduled prior to this point in time.

The first neurosurgeon I went to about my “condition” was in Portland. It was in the summer of 1977. He said to me, “You may as well hang up the guitar. You’ll never play it again.”

Lenny at The Riverboat (1968) in Toronto, Canada. (Photo permission and courtesy of Art of Life Records.)

This news came as a complete and utter shock to me. It just confirmed what I felt was happening to me. I completely lost my sense of balance. I lost my marriage. I lost my home. I lost everything that had any meaning to me at the time. I lost my ability to be touched by music. I lost my capacity to play it.

I was ashamed of myself.

I became homeless for two years. Then a family in South Portland took me into their home for the following two years.

I never wanted to play the guitar again, let alone listen to it be played. Ditto to any form of musical expression.

It was during this dark time (the spring of 1980), an acquaintance of mine from Los Angeles, invited me to go with him to hear a guitarist named Lenny Breau. At first, I absolutely refused to go, let alone listen to him extol the virtues of Lenny’s artistry.

“Look,” Jim told me, “Lenny’s trying to get back on his feet. He’s surrounded by vultures who just want to take advantage of him. He can use an audience who just enjoys hearing him play.”

I was told about Lenny’s country and western roots through his parent’s music. His ties to Maine, especially the Lewiston/Auburn area, were deep and people loved his parent’s music. Lenny started playing with his mother and father when he was a mere child.

Lenny is the greatest guitar player in the world today. I think he knows more guitar than any guy that’s ever walked the face of the earth, because he can play jazz, he can play a little classical, he can play great country—and he does it all with taste.

— Chet Atkins (1924–2001), Frets, October 1979

When they moved to Winnipeg, Canada their fame blossomed even more. They became well known throughout Canada. Lenny’s own musical career blossomed here as well. His reputation grew to legendary status.

None of what Jim told me about Lenny’s extraordinary playing abilities touched me. I was too miserable and possessed by my own guilt and the demons pursuing me into oblivion to care about hearing another artist’s work, let alone going to listen to Lenny play. However, when I heard that Lenny was going through very difficult times, I became interested in hearing more about what he was experiencing. His father, Harold John Breau (also known musically as Hal Lone Pine), died in late March of 1977 due to the ravages of alcoholism. Lenny was fighting his own demons, too, especially drug and alcohol addiction. He had also lost his own marriage as well. I understood what these losses could do to you.

Despite my utmost reluctance to go see Lenny perform, even more so because I was being told that he was a virtuoso, I gave in to Jim’s pleas. He just wore me out listening to him extol Lennie.

Lenny remains the Pacific Ocean of fingerstyle jazz guitar inspiration. Unmatched technique, stylistic diversity beyond belief and that musical wistful intelligence that I doubt we’ll ever see again. It’s great to have a musical hero you can still be amazed at after 40 years of study.

— Kent Hillman, drummer, percussionist & composer

It was a week day that Jim and I went to Brunswick to go hear Lenny. Jim drove his car.

When I found out that we were going to Peter Balis’, The Cellar Door, in Auburn, Maine, I had a panic attack. Peter was also the owner of No Tomatoes, the restaurant that was upstairs, street side, from where Lenny was scheduled to play. I had played at “No Tomatoes” in better days. I just about opened the car door to get out and walk back to Portland when I realized where we were going.

We arrived early. For some reason, I remember where we parked. It was warm outside. The sun was still shining strongly. Inside the tavern, we found a table that was close to where the performers were going to play. The bassist, Les Richards, and the drummer, Steve Grover, were already set up on stage.

My first sight of Lenny was seeing him shyly getting up on stage, sitting on a stool, and putting an electric guitar on his lap. He tuned his guitar briefly using harmonics and riffing off them as he went from the sixth to the first strings and back again. Steve tested out the drums, and set them in a more precise and comfortable position; Les seemed ready to go.

Lenny said something to them under his breath, counted out the beat, and they started their first set playing the Lorenz/Hart tune, “My Funny Valentine” (1937).

Halfway into it, I lost track of time and became stunned at what I was hearing. As a matter of fact, I wasn’t sure what I was hearing. Changes in time. Changes in keys, modal chord structure lines moving in and out of the melody line and then going off into some pure form of ethereal exploration. Extended solos between Lenny, Les and Steve.

He dazzled me with his extraordinary guitar playing . . . I wish the world had the opportunity to experience his artistry.

— George Benson, American musician, guitarist and singer-songwriter

An hour went by and I was totally entranced by what I was listening to in front of me.

Lennie hardly said anything, although he did sing a couple of songs in a voice that sounded very raspy and high. I didn’t mind his singing. I was amazed he could sing in complement to his incredible playing. I think one of the tunes he sang was “Salt and Pepper”.

The trio took a break, came back and started off with a Bill Evans’ tune, “Funkallero”. Lenny would smile, frown, grimace and then disappear in a flurry of single note lines accompanied here and there with modal chord changes tastefully interchanged with the melody lines he was laying down, seemingly, all around us.

They played the Victor Young song‡, “Stella by Starlight”, Elizabeth Cotton’s‡ “Freight Train”, Johnny Mercer’s version of “Autumn Leaves” (1947), Lenny’s (1978) composition “Minors Aloud”, and ended up with a couple of Coltrane songs, the second one being “Impressions” (1962).

When the gig was over, Jim went up to Lenny and brought him over to the table where we had been sitting. He introduced me to Lenny. Lenny sat down and started talking with us. The conversation ran so well and comfortably that when the place shut down we went to a nearby diner and had something to eat.

I discovered that Lenny did not sight read, which is mostly how I had gotten by playing the classical guitar. I said to him that I didn’t think that mattered all that much, especially after hearing what he had just done that evening. He was doing stuff I had never heard done at all by anyone.

Lenny and I were in New York, and on a particular evening, decided to drop in at Birdland to hear John Coltrane. (Coltrane was about to record, or had just recorded his album John Coltrane Live at Birdland.) After listening to a set, Lenny, who invariably carried his acoustic guitar with him, approached Coltrane and asked if he could sit in. I recall John looking Lenny up and down and at some of the group and they nodded their consent. [ . . . ] When Lenny sat in, after plugging his guitar into one of the speakers, he initially just played chords to get a feel for what was happening. In the following number, when Lenny’s turn came to play, the effect was electrifying. Coltrane leaned over with eyes wide–open, looked at Lenny’s hands, and smiled. During the remainder of that session, which lasted for at least another two hours, Lenny played with authority with the great John Coltrane, and on many of his licks, Lenny led the charge.

— George B. Sykornyk (July 31, 2003), excerpted from liner notes to Lenny Breau: The Hallmark Sessions, 2003, Art of Life AL 1007-2.

From that point onwards, I tried to go to as many of Lenny’s performances as I could. I’m not sure that we became fast friends, but there were several nights and days when I spent the time with him and watched him play in public and practice at the place where he was staying at that time.

Canadian Music Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony brochure (1997).

He talked a lot about tonal musical exploration; in other words, painting with sound and chord voicings on the guitar that he picked up from hearing Bill Evans play. He talked about French Impressionism and how he loved the work of Renoir.

Lenny talked about how he took care of his right hand nails, how to play chordal harmonics, mastering scale and modal patterns, and the mystery, passion and romance he had with music.

When he learned that I was a classical guitarist, he took out his classical guitar and played a couple of Bach compositions flawlessly. He then spent a couple of hours talking about and playing flamenco music. Again, I couldn’t believe how well he mastered the classical and flamenco styles of playing.

One day I was at Chet’s and he told me he wanted me to meet this guitarist. Lenny was upstairs playing. Even before I made it half way up the stairs I was hearing things that were astonishing. Ten minutes later I was sitting with Lenny who began to play harmonics such as I have never heard in my life, and then I started learning right there and then. Chet, and he mentions it in his autobiography, always regretted that he didn’t film that session. To this day, there is no one in the world who can do what Lenny did and we are all indebted to his legacy.

— Tommy Emmanuel

I saw him do some absolutely stunning left and right hand techniques that I had never seen anyone do. When he told me he had learned how to do it all by himself and listening to records, I was speechless. The amount of self–study, practice, correction, evaluation and appraisal of what he was trying to accomplish in playing flamenco alone takes years to achieve, hour after many hours of practicing.

He is the only guitarist I have ever known to play two melodies at the same time, in different time signatures and in different keys.

I think that Lenny was very similar to Van Gogh. Both men were deeply immersed in their own artistic worlds. They saw the world and felt it in ways that most human beings do not because they had a hypersensitive medium they used to explore it. They were extremely driven. They were lost in their explorations of creativity. They kept reaching for and attaining greater and greater levels of fluency in expressing themselves. Both men shared a kindred spirit in reaching out toward their respective artistic vision.

Both descended into deep depression, even madness. Both were not of this world, their feet stepped on ground in another realm of reality. Their eyes saw possibilities we only recognized and remembered when they brought them to us musically and visually. They used the palette of their awareness to draw textures, sounds, colors and intonations of beauty, darkness, fear and love they experienced around them.

I have found a better player than I am.

— Merle Travis, describing a then 12–year–old Lenny

I marveled at how Lenny could get stoned and then play into the stratosphere of outstanding lyrical beauty. I did not understand how he could do the hard drugs available to him and then play at a level no one I have ever known ever realized.

Lenny at Bourbon Street (1983) in Toronto, Canada. (Photo permission and courtesy of Art of Life Records.)

When Lenny left Maine in 1981 to move to Stockton, California, I was at a loss not to hear him play any more nearby.

My life started to come together then. He helped inspire me to listen to the guitar again. His love of playing, his love of music and his love of the guitar actually helped save my life. Due to our talks about music, about artistry, and over our creative passion in playing the guitar, I decided to go back to school and study how the performing and visual arts can be used to enhance an educator’s professional development.

Lesson from Lenny: I thought that my music was my art. I built my whole life around that concept. I learned, instead, that my life was my art.

Six days before my birthday in 1984, I was stunned when I heard that he had been found dead in the deep end of a rooftop swimming pool in Los Angeles. People who knew Lenny at that time told me that he had been murdered.

The world lost a one–of–a–kind genius. We are blessed to have the recordings that were made of his playing. Truly, though, these recordings do not approach the quality of playing I heard him attain. Jazz, classical, bebop, folk, rock, standards, flamenco, country & western, and his own brand and style of cool, were all combined by him into a fusion of sound unlike any other musician in this world.

Through his own form and exploration of musical storytelling, Lenny created a spiritual soundscape. I think he was an apostle of the guitar; a prophet of the strings. He didn’t just play music. He played prayers, ragas of the soul from a world he saw quite clearly . . .

†Thanks to Mr. Paul G. Kohler, President, Art of Life Records

Related Links on Lenny:

http://www.guitarworld.com/lenny-breau-forgotten-genius

http://lennybreau.com/lbart2.html

http://www.sandguitars.com/artists/breaul/artistpage.htm

http://www.softandgroovy.com/lenny-breau.html

Recommended Reading:

Forbes-Roberts, Ron. One Long Tune: The Life and Music of Lenny Breau. Denton, Texas: University of North Texas Press, 2006. Print.

Routhier, Ray. “Maine-born jazz guitarist Lenny Breau remains influential 30 years after his killing.” Portland Press Herald Sunday, 10 April 2016. Web. 12 Apr. 2016. <http://www.pressherald.com/2016/04/10/maine-born-jazz-guitarist-lenny-breau-continues-to-influence-and-amaze-more-than-30-years-after-his-death/>.

Notes:

‡“Stella by Starlight,” written by Victor Young (1900–1956) was first played as an instrumental in the 1944 movie, The Uninvited, which was directed by Lewis Allen and released by Paramount Pictures. Ned Washington (1900–1976) added lyrics to it in 1946.

‡Elizabeth “Libba” Cotten (née Neville) (1893–1987) was a left handed guitarist. She would play a right–handed guitar upside down and play it in that fashion. As a result of her holding the instrument this way, she developed a style of playing known as Cotton picking, where the melody lines were played with her left hand thumb, while her left hand fingers played the bass lines. Besides being an American folk and blues musician, she was also a singer–songwriter.

If you enjoyed reading this post, please share it with others.

Disclosure of Material Connection: I have not received any compensation for writing this post. I have no material connection to the brands, products or services that I have mentioned here. I am disclosing this information in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.”

© 6 April 2016 by A. Keith Carreiro

4 comments. Leave new

Anyone musician who was pretty much an unknown who had the guts to ask Coltrane at the Birdland stage if he could “sit in” with the master was either sickening delusional or skillfully brilliant beyond comprehension. I was somehow unaware of master guitarist Lenny Breau so thank you for the info plus a glimpse into one the golden ages of jazz. I will tell a few guitarist about Lenny.

Dr. Keith: I am sorry to hear that you had to give up your guitar playing over physical concerns but it looks like fate opened up other doors. Keep writing!

Hi, Robert,

You make an excellent point about anyone approaching Coltrane and asking to sit in with him on a gig. Lenny did not often demonstrate such chutzpah. This occasion was a rare occurrence. I guess the saying that when one door shuts another opens is true. I’m praying the door to successful acceptance of my writing continues to open.

This is a fantastic blog Keith, and a wonderful tribute to Lenny Breau! You are an excellent writer!! You are also an exellent guitarist! I can’t wait for the release of the Penitent part 1…

Thank you, Carolyn. Glad you like it. Lenny meant a lot to me.